Exploring the Mandelbrot Set in OCaml

There’s something deeply satisfying about a piece of math that produces infinite complexity from almost nothing. The Mandelbrot set is exactly that — a simple equation, iterated over and over, that draws the boundary between order and chaos across the complex plane.

I built an interactive viewer for it in OCaml using SDL2. The entire thing fits in a single file. This post walks through the math that makes it work.

Complex Numbers in 30 Seconds

A complex number has two parts: a real part and an imaginary part. We write it as , where . You can think of complex numbers as points on a 2D plane — the real part is the x-axis, the imaginary part is the y-axis. This is called the complex plane.

The key operation is multiplication. When you multiply two complex numbers:

Geometrically, multiplication stretches and rotates. Squaring a complex number doubles its angle from the origin and squares its distance. This stretching-and- rotating behavior is exactly what makes the Mandelbrot set interesting.

The Definition

The Mandelbrot set is defined by a single recurrence:

Start with . Pick any point on the complex plane. Now iterate: square , add , repeat. One of two things happens:

- The sequence escapes — grows without bound, shooting off toward infinity.

- The sequence stays bounded — never exceeds some finite value, no matter how many times you iterate.

The Mandelbrot set is the set of all points for which the sequence stays bounded. That’s the entire definition.

The Escape Condition

In practice, you can’t iterate forever. But there’s a useful shortcut: if ever exceeds 2, the sequence is guaranteed to escape. The magnitude , and to avoid the square root we check:

This is why the code uses 4.0 as the threshold:

let iterations x0 y0 =

let c = { Complex.re = x0; im = y0 } in

let z = ref Complex.zero in

let iter = ref 0 in

while !iter < max_iteration

&& (!z).Complex.re *. (!z).Complex.re

+. (!z).Complex.im *. (!z).Complex.im <= 4.0 do

z := Complex.add (Complex.mul !z !z) c;

incr iter

done;

!iterFor each pixel on screen, we map it to a point on the complex plane and count

how many iterations it takes for to exceed 4. If it never does within

max_iteration steps, we assume the point is in the set.

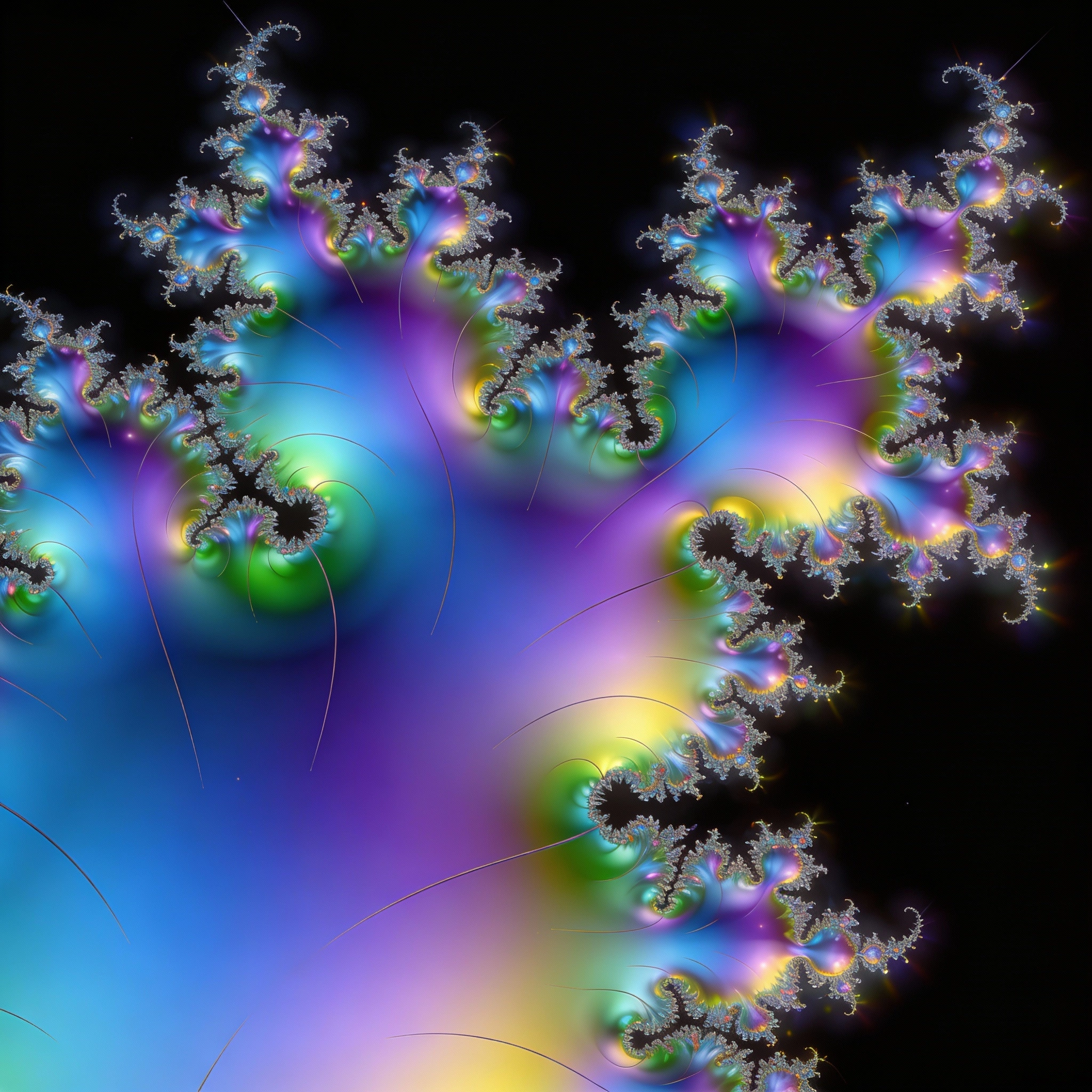

Why the Boundary Is Fractal

The boundary of the Mandelbrot set — the edge between points that escape and points that don’t — is where things get strange. Points near the boundary take many iterations to escape. Points just barely inside the set take many iterations before settling into a bounded orbit. This sensitivity to initial conditions means that no matter how far you zoom in, you find new structure. The boundary has infinite detail at every scale.

This is what makes it a fractal. The boundary’s Hausdorff dimension is 2, meaning it’s so convoluted that it’s effectively as complex as a filled area despite being a one-dimensional curve.

Coloring

Points inside the set are colored black — they never escape. For points outside the set, the number of iterations before escape gives a natural way to assign color. Low iteration counts (quick escapes) get one color; high counts (slow escapes) get another. The coloring function maps the iteration count to an RGB value packed into ARGB8888 format for SDL2:

let color_of_iter n =

if n = max_iteration then

0xFF000000l (* black — in the set *)

else

let v = int_of_float (255.0 *. float n /. float max_iteration) in

Int32.of_int (0xFF000000 lor (v lsl 16) lor ((v / 2) lsl 8) lor (255 - v))This produces a gradient from blue (quick escape) through green to red (slow escape), with the set itself in black. More sophisticated coloring schemes exist — smooth iteration counts, histogram equalization, orbit traps — but this simple mapping already reveals the structure.

Rendering with SDL2

The viewer uses SDL2 via OCaml’s tsdl bindings. The approach is straightforward:

create a streaming texture with ARGB8888 pixel format, lock it to get a Bigarray. int32 buffer, write every pixel, unlock, and present. One frame, one pass, no per-

pixel draw calls.

let redraw renderer texture xmin xmax ymin ymax =

let (pixels, pitch) =

Sdl.lock_texture texture None Bigarray.int32 |> or_exit

in

draw_mandelbrot pixels pitch xmin xmax ymin ymax;

Sdl.unlock_texture texture;

Sdl.render_clear renderer |> ignore;

Sdl.render_copy renderer texture |> ignore;

Sdl.render_present rendererSDL’s coordinate system has at the top of the window, which is the opposite of the mathematical convention. The code compensates by mapping SDL row 0 to and row to .

Zooming and the Infinite Detail

The viewer supports interactive zoom. Click a point and the viewport shrinks by half around it, doubling the magnification. This is where the fractal nature becomes tangible — you can zoom in dozens of times and still find new spirals, miniature copies of the full set, and filaments connecting them.

Mathematically, zooming just changes the window on the complex plane. The computation is identical at every scale; only the coordinates change. The set itself has no preferred scale.

At extreme zoom levels, floating-point precision becomes the limiting factor.

Standard 64-bit float gives roughly 15 significant digits, which allows roughly

times magnification before the pixels stop resolving new

detail. Going deeper requires arbitrary-precision arithmetic or perturbation theory

— topics for another day.

Building and Running

The project requires OCaml, opam, and SDL2:

# install SDL2

sudo apt-get install libsdl2-dev # Debian/Ubuntu

brew install sdl2 # macOS

# build and run

opam install . --deps-only

dune exec mandelbrotClick to zoom in. Press +/- to zoom at the cursor, hjkl or wasd to pan,

r to reset, q to quit. The source is on GitHub.

Further Reading

The Mandelbrot set sits at the intersection of complex dynamics, number theory, and computer graphics. A few starting points for going deeper:

- Benoit Mandelbrot’s The Fractal Geometry of Nature — the book that started it all

- The Ewing and Schober proof that the Mandelbrot set is connected

- Mu-Ency — an encyclopedia of the Mandelbrot set and its features

- Perturbation theory for deep zooming: the technique behind modern ultra-deep renderers